The Little-Known Origin Of TV Dinners

TV dinners are making a comeback. Demand for frozen foods has been on the rise ever since the COVID-19 lockdowns began in 2020. Even with many facets of the food supply line returning to normal, the American Frozen Food Institute reports that sales of frozen meals were up 8.6% in 2022 and show no sign of slowing down. Just a few short years ago, the TV dinner was seen as a nostalgia-inducing relic from the age of "Leave it to Beaver" and "Father Knows Best," but with its modern resurgence in full swing, it's time to take a deeper dive into the history of this all-American meal.

The origins of TV dinners begin with Clarence Birdseye, the father of the modern frozen food industry. A New York native and former biology major, Birdseye's life changed forever in 1912, when he took a job as a fur trader in the Canadian province of Labrador. There, he saw how the indigenous Inuit used the naturally frigid climate to freeze fish, and when frozen rapidly, the fish would not suffer any loss in quality when it was ultimately reheated for a meal. This inspired Birdseye to invent the modern method of flash-freezing, wherein food is frozen under high pressure, and in 1924, he founded Birdseye Seafoods, selling frozen fish in freezer cases he had specially built for local markets. Previous methods of freezing meat resulted in a loss of texture and flavor, but Birdseye's flash-freezing method paved the way for a frozen food explosion.

How WWII and a disastrous Thanksgiving brought us TV dinners

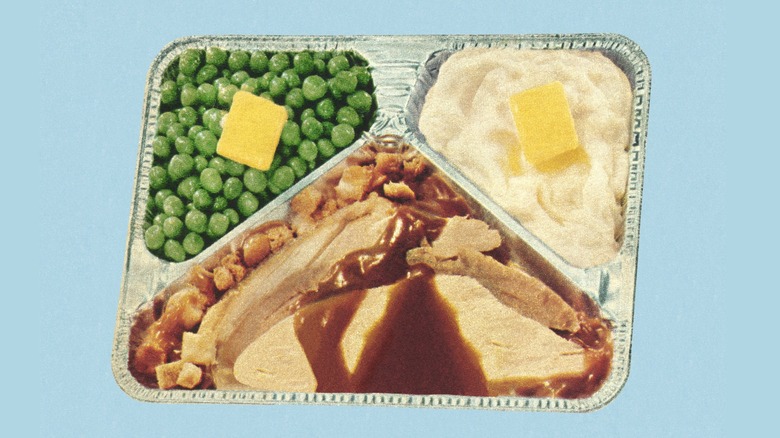

For the first few decades after Birdseye's invention, frozen foods had a very limited audience. Big developments were made near the end of WWII when Maxson Food Systems Inc. developed a line of frozen meals for members of the military. Dubbed "Strato-Plates," they were just what you'd expect from a TV dinner: a plastic plate with three compartments, one for meat, one for vegetables, and one for potatoes, but it was intended to be eaten on airplanes, not in front of the tube. A similar innovation from the 40s, Jack Fisher's FridgiDinners, was marketed to bars and taverns that didn't have a full kitchen or cooking staff.

In 1949, a pair of brothers from Pittsburgh founded Frozen Dinners Inc., and within five years, they sold over 2.5 million meals to consumers in the Eastern U.S. However, the TV dinner made a breakthrough in 1953, when the Nebraska-based Swanson company experienced a disastrous lag in Thanksgiving sales, leaving them with a surplus of 260 tons of turkey. A company executive hit on the bright idea to package portions of the leftover bird with sides of cornbread stuffing and sweet potatoes and sell them in aluminum trays for easy reheating in the oven. A bacteriologist named Betty Cronin was instrumental in helping Swanson perfect the method so that customers could avoid food-borne illnesses. However, when it comes to the executive who had this idea in the first place, things aren't so clear.

Who deserves credit for the TV dinner?

For decades, credit for the invention of TV dinners was given to Gerry Thomas, a Swanson salesman who was just a few years into the job when the turkey crisis happened. As the story goes, Thomas took a plane flight where he was served a meal in a tray, and it gave him the idea to repackage Swanson's surplus meat in a partitioned aluminum tray, which he sketched and presented to his bosses. The company seized on two of the most important developments of the 1950s — the television and the surge of women into the workforce —to market their frozen meals as "TV dinners," something a housewife who just got home from work would whip up in a few minutes and enjoy while watching sitcoms with her family.

This version of the story was widely accepted, and Thomas was even honored by the American Frozen Food Institute in their Frozen Food Hall of Fame. However, in 2003, reports surfaced that challenged Thomas's claim. Descendents of Swanson executives Clarke and Gilbert Swanson claimed that the brothers came up with the idea themselves, and Thomas stole the credit. It's even said that Gilbert Swanson experienced the same airline epiphany that Thomas claimed to. This version of events is also backed up by Betty Cronin, whose role in the invention has never been disputed. The Swanson brothers both died in the 1960s, and Gerry Thomas passed away in 2005, likely taking the real story with him.