Sparkling Water Is Older Than The United States Of America

The name Joseph Priestley may spark some dim memories from high school chemistry class, since he's credited with the discovery of oxygen among other gasses. But this 18th century English scientist, with wide-ranging interests, was also responsible for a product you've most likely enjoyed on a regular basis: sparkling water. Whether you prefer your mixed drinks with seltzer, tonic water, or club soda, it's Priestley (and the previous work of other scientists) you have to thank for inventing the method of artificially injecting carbon dioxide into water, which eventually led to the rise of the soft drink industry.

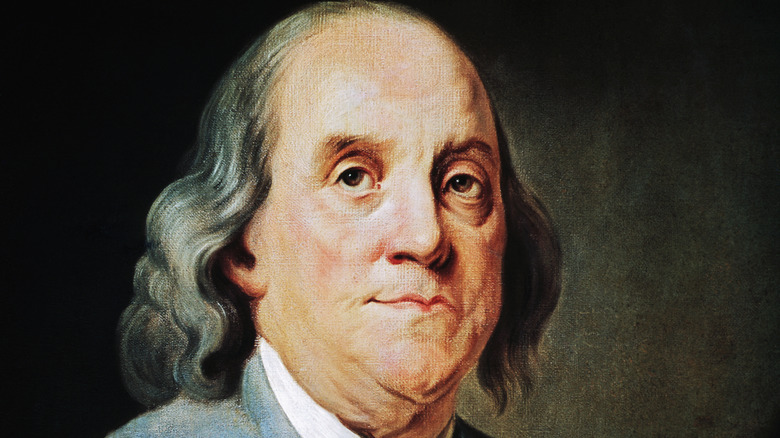

Priestley, a Unitarian minister, discovered the process by accident while working on various scientific experiments at a brewery in Leeds, England, in 1767. This was nearly a decade before the Declaration of Independence in 1776 that birthed the United States of America. And it was Founding Father Benjamin Franklin who encouraged Priestley's pursuit of science, which would eventually lead to Priestley producing sparkling water via an invention he perfected in 1772.

An American founding father inspired Priestley

Joseph Priestley first met Benjamin Franklin at a London coffee house in 1765 during a weekly club of intellectuals and scientists called The Club of Honest Whigs. At the time, Priestley was a minister and a schoolteacher. Franklin pushed Priestley to pursue science and conduct his own experiments. Two years later, Priestley discovered that by placing a shallow bowl of water just above a vat of fermenting beer, it resulted in the water being infused with the carbon dioxide rising from the beer vat.

By 1772, Priestley had developed a working system for producing sparkling water and published a pamphlet, "Directions for Impregnating Water with Fixed Air," which described in detail how the machine worked. "If this discovery ... be of any use to my countrymen, and to mankind at large, I shall have my reward," Priestley wrote. His invention used sulphuric acid and chalk to produce carbon dioxide that was collected in a pig's bladder and then injected into an inverted water-filled bottle that sat in a bowl of water, per the McGill University Office for Science and Society. For Priestley, the whole point of creating artificial sparkling water was for its perceived medicinal benefits. At the time, natural sparkling water was considered a health tonic with supposed curative effects of all kinds.

Sparkling water was considered a health tonic

For centuries, people believed that natural sparkling water could help alleviate a variety of ailments, including scurvy, a disease that especially plagued the British Royal Navy, whose sailors suffered horribly from it. In his work on the subject, Priestley specifically discussed scurvy and contacted the Admiralty, which oversaw the navy, about his invention. As it turned out, sparkling water didn't cure the disease, which stems from a lack of vitamin C, but at least we ended up with a delicious beverage.

Soon after Priestley published his guide to producing sparkling water, other scientists improved on the original design. Then, in 1783, Priestley's design was reworked to mass-produce sparkling water, by Jacob Schweppe — the founder of the company that still produces carbonated drinks today. By the 19th century, Priestley's discovery had birthed a huge industry, not just in sparkling water but for various sodas that also claimed to have health benefits, such as Pepsi, which was named after indigestion. Thankfully, today your SodaStream doesn't require a pig's bladder to work.