Jell-O Salads Once Represented Wealth And Status

Ah. Jell-O. The pre-packaged jiggly dessert that jiggled right into our hearts. And of course, the foundation of Jell-O salads. But that wasn't always the case. Once upon a time, Jell-O — or more specifically, gelatin, the building block of the Jell-O and the Jell-O salad — was once a staple of luxury meals, like Napoleon-Bonapart-and-King-George-IV-kind-of luxury meals. Naturally, this sort of spread wouldn't be possible were it not for the fact that gelatin managed to impress the tastebuds of celebrity chefs, like Marie-Antoine Carême, a contemporary of King George and Napoleon Bonapart.

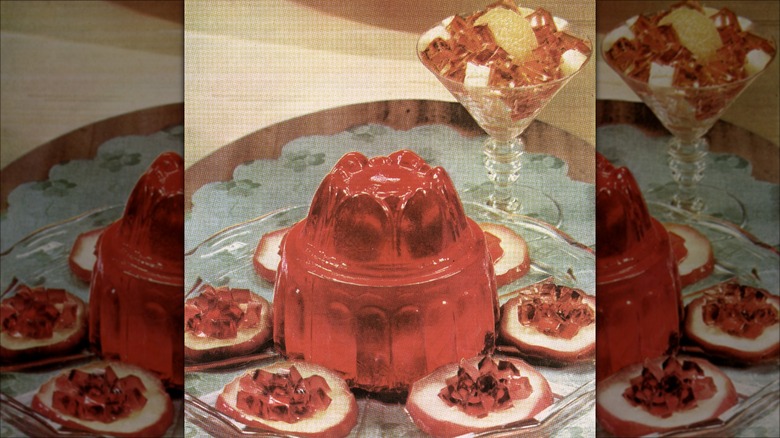

If Jell-O, food of kings is difficult to believe, consider this. One of Carême's signature gelatin concoctions involved him making elaborately sculpted centerpieces from the jiggly stuff. To put this into perspective, Atlas Obscura calls such a gesture the modern equivalent of a "master chef placing towering Jell-O concoctions at a royal wedding or the French Laundry." (That's the three-Michelin star restaurant in California, not a French laundromat, to be clear.)

It took a while for a historical through-line to form between the King's table and the Jell-O salads that dominated luxurious meals of the early part of the 20th century, but there's a through-line. By the time Mrs. John E. Cook introduced her Perfection Salad to the world via a Better Homes and Gardens and Knox Gelatin contest, the foundation for Jell-O salad as a luxury item had already been laid centuries before her invention.

The ancient history of gelatin

This is a head-scratcher for people looking at Jell-O salad with 21st-century eyes. However, gelatin-as-a-luxury meal stretches back in time, farther than most people realize, farther than even Marie-Antoine Carême; it goes all the way back to Europe in the 1400s. In those days, making gelatin was, most kindly put, tedious at best. Only those with considerable wealth could afford the necessary kitchen staff required to turn animal bones, cow hooves, and other unmentionable parts into collagen, the building blocks of gelatin.

The snob appeal of gelatin-based meals can't be overstated. Put it this way. Imagine inviting your frenemies over to your country home — your third country home — for a weekend of show-and-tell-the-wealth, and knowing that if you wanted to truly make your contemporaries green with envy, you'd better plan on serving an over-the-top molded gelatin display in all its jiggling glory.

Eventually, those impressive jelly dishes got some serious street cred with the upper crust on the other side of the Atlantic, largely via Thomas Jefferson's influence. He encountered gelatin dishes in France when he was doing diplomatic work there during the late 1700s. Jefferson must have liked it. A recipe for wine jelly — aka wine gelatin — appears in some of the historical documents for Monticello, the former President's home. And if recipes for it were important enough to preserve in his house documents, then it was presumably also important enough to serve at his own impress-your-friends dinner parties.

Jell-O becomes a mass market thing

It wasn't until 1897 when Pearle Wait evened the playing field, making the possibility of dinnertime luxury accessible to the masses in the form of Jell-O salads and tomato aspics. The carpenter-turned-Jell-O-inventor took gelatin from a plain, nearly lifeless ingredient to a sweet, powdered, and colorful Jell-O. No one knows where the food coloring came from, but the flavors for his Jell-O arose from fruits like strawberries and oranges.

Pearle Wait eventually trademarked his invention and its name: Jell-O. However, he didn't make much money for his trouble. After some time, Wait sold the concoction to Genesee Pure Food for $450, according to Kovel's Antique Trader. The food company, which would become General Mills one day, undertook an ad campaign to tempt homemakers to make Jell-O recipes. As it happened, homemakers of the 19th century were keen to act on their dreams of upward mobility by trying their hand at making molded Jell-O displays, just as their wealthier counterparts had.

It was only seven or eight years after Wait invented Jell-O that Mrs. John E. Cook's salad garnered attention. It's even more difficult to believe that the Better Homes and Gardens contest's third-place winner inspired generations of women to suspend such delicacies as shrimp, hard-boiled eggs, cucumbers, celery, chunks of chicken, and more in blocks of Jell-O. But the advertising and the infinite number of Jell-O salad recipes had an effect. By 1907, a million dollars worth of Jell-O had been sold, (per CNN).

Jell-O in the 20th century

At the height of the Jell-O craze during the early 20th century, all manner of flavors existed, and not just sweet ones. Italian salad, celery, seasoned tomato, and mixed vegetables counted among the savory Jell-O flavors homemakers could buy. It got to the point where said homemakers consulted little booklets put out by the Jell-O company that taught them Gelatin 101 tricks, like what kinds of fruits float — apple cubes, sliced strawberries, and marshmallows, for the record — and which foods didn't. Cooked prunes, anyone?

While this might seem odd, it made sense at the time. If you were making a luxury display consisting of different foods, it's best to know that expensive foods like shrimp sink to the bottom of the Jell-O while apples float at the top. Homemakers still tried to embrace Jell-O recipes as proof that one could still make a luxury meal, even if it meant using war rations and leftovers to do it.

Given that Jell-O recipes took up one-third of the real estate in 20th-century cookbooks, Jell-O salad eventually became too ubiquitous and thus, a difficult sell as a luxury item, especially given the emphasis on economy that showed up in 1950s food trends. Jell-O-salads-as-luxury-items were on their last legs. Too many people had used Jell-O salad as a wartime food preserver for it to be anything but pedestrian to most homemakers by the mid-twentieth century.