Before Store-Bought Milk Was A Thing, There Was The Milkman

Milk delivery and the milkman are back again, thanks to the effects that the COVID-19 virus had on mobility in society. That pesky virus did what no amount of nostalgia marketing featuring Rockwellian imagery could do: It pulled milk and dairy purchases away from weekly trips to the grocery store and put them back in the stomach of the delivery wagon.

"I think people forget how frequent food deliveries were in the late 19th and early 20th centuries," said food historian Sarah Wassberg Johnson. "Whether direct from grocers or via mail order services like Sears & Roebuck, people did get daily or weekly deliveries."

Things have changed since the old days of the milkman, of course. Amazon food deliveries are more common than those from Sears & Roebuck. Plastic or cardboard cartons of milk have replaced the glass bottles of old. That those deliveries included milk and dairy products at all is pretty impressive, given that man's earliest ancestors found the substance nearly indigestible.

But what was once incompatible with the human digestive system has become such an important food source that a whole system has been set up for the delivery, processing, and consumption of it. And for many of us, the milkman of yesteryear and today is the epitome this system, including industry advancements brought on by their jobs and the nostalgic feelings the millions of milk carriers have left in their wake over the decades.

Milkmen became a thing after people stopped keeping cows

The first recorded instance of milk delivery in the United States happened in Vermont in 1785. While it's true that major waves of urbanization hit a crescendo in the 19th century, that first delivery of milk pointed to the things to come. When most people still lived on small farms, getting milk and dairy products wasn't an issue. Usually, those living in rural areas kept a cow or two on their land, which provided them with the milk and cheese they needed to get by.

However, as people begin to live in more urban areas during the 19th century, the practice of keeping a personal cow for milking purposes became impractical. People simply didn't have room to keep a cow in their more urban environments, nor did they have the benefits of modern refrigeration. But that wasn't all. It was also time consuming to keep a cow.

As Sarah Wassberg Johnson pointed out, "While they are producing milk, cattle have to be milked twice a day," and what's more, unpasteurized raw milk is "highly perishable."

Enter the milkman (and of equal importance, the iceman, since ice was the fridge hack of the era). Having someone who could deliver milk (and fresh ice) daily guaranteed that people got the milk and dairy supplies they needed. It also meant that farmers weren't left having to dump milk because it hadn't been consumed by baby cattle nor the farmers' neighbors.

Animals were often involved in deliveries

The automobile wasn't invented until 1886 when Carl Benz of Mercedes Benz asked for a patent for his wagon powered by a gas engine instead of by horsepower. That means 101 years passed between the day that the first milkman made his deliveries and the invention of the automobile. And yet, milk delivery still happened, thanks to animal power, human and non-human alike.

If they didn't deliver the goods using their own power, care of a bicycle or their legs, the milkmen of bygone eras usually hitched their milk wagons to horses. However, attaching the cart to a couple of big dogs wasn't out of the question, either. Some of those animals possessed some pretty impressive and useful skills, too. As Smithsonian Magazine pointed out in a 2012 article, "When yesterday's milkman walked between houses, his horse would quietly keep pace with him on the street."

Moreover, the practice of tapping animals for help with daily milk deliveries didn't end when automobile use went into full swing. Indeed, having a non-gasoline-powered option proved helpful during World War II. Horse-powered wagons picked up the slack when gas rationing kicked in toward the end of 1942. Rubber for tires also turned scarce for the same reason that gasoline did. However, horses usually walked so slowly that wearing out the milk wagon's tires wasn't an issue. And of course, the dearth of gasoline presented no trouble, either.

Milk delivery is cow-to-table

Many of the modern age milkmen deliver milk from local dairies that guarantee that it's 48 hours or less from the time the cow is milked until the time it's on the table. Consumers are closer to the beginning of the supply chain, which is a definite advantage. Nowadays, people worry about bacteria like E. coli in the milk supply and dealing with unscrupulous food dealers, so the fewer stops the milk needs to make between cow and table, the less likely it is for these issues to crop up. Consumers know where their food comes from and suppliers know that, too.

However, this wasn't always the case throughout the history of milk delivery. The milk supply became a particular concern in the 1800s. According to Alex Prizgintas, President of the Woodbury Historical Society and Proprietor of the Orange County Milk Bottle Museum, from the 1840s to the 1860s, swill milk, "a vile product provided by diseased cattle kept in unsanitary city stables," caused numerous infant deaths in New York City.

It took some time for doctors to find the culprit, which turned out to be cows in urban dairies that had been fed the leftover mash from distilleries. Ironically, all of this led to the country's first shipment of fresh milk coming by railroad to the cities from places like Orange County (where Prizgintas is from) in 1842.

Milk delivery and the milkman were big in Wawa's history

Though Wawa convenience stores now sell a bit of everything from sandwiches to gas, it was primarily a dairy outfit at the turn of the 20th century. Given that it was founded in Pennsylvania during a time when plenty milk of production came out of that region, it's probably no surprise that milk formed the foundation on which Wawa built its fortunes.

Because the swill milk scandals had marred the reputation dairy industry in the mid- to late-1800s, the dairy businesses that followed felt the effect, including Wawa. Because of this, the company prided itself on producing healthy milk. Many doctors offered their endorsements of Wawa's milk. This "doctor certified" milk bolstered the company's standing in the industry, according to the Times Herald.

Wawa's milk delivery system included a legion of milkmen, first in horse-drawn carriages and then in Wawa's motorized delivery trucks. The quality of Wawa's milk and dairy products, along with the people who delivered them, played a big role in the company's reputation and its growth until the 1960s.After that, the company restructured to keep up with the proliferation of grocery stores that popped up around the country, which eventually left milkmen in the company's past.

Bottles became necessary to keep the gunk out of the milk

Gleaming glass milk bottles became synonymous with the milkman of old. However, the earliest attempts at milk delivery didn't include bottles at all. The milk delivery person carried large cans around in his truck. (Most milk carriers were men). Once he got to his stop, the home's proprietor would produce a jug or a container and in would go some milk. The practice of ladling fresh milk into individual containers or jugs meant that there was also the possibility of finding gunk in the milk, which ranged from animal hair to insects.

The invention of the milk bottle in Brooklyn in 1878 by George Henry Lester revolutionized the milkman's job for a number of reasons. "[It] not only allowed milk to be transported in a sanitary fashion but, also gave farmers more economic control by allowing them to retail milk directly to the consumer," Alex Prizgintas explains.

But the milkmen who carried the jars around on their regular routes benefited from the invention of milk bottles, too. Having glass bottles to carry the milk made transporting easier. This simple technological advancement also allow the milkman to create a more accurate tally of how much milk each family got.

Milk boxes were built into houses

For some homes, the daily milk delivery even dictated the house's design. At the height of the milk delivery era, some homes came equipped with a milk box in front, usually insulated, sometimes made of metal. Some of these cubbies were even built into the home's architecture and facilitated milk delivery via a double-door system. The milkman placed the bottles of milk and any other dairy products that the homeowner ordered, like butter, in the box via the outside door. Inside the house, the homeowner accessed the dairy delivery via box's second door, which was inside the house.

The milk box served as a mailbox of sorts, too. The family's daily milk order was left in the box for the milkman. When billing time rolled around, the milkman left the bill in with the milk delivery. The customer then left money to pay the bill in the milk box, which the milkman picked up once he came back around.

However, many homes didn't come with milk boxes. To get around this, some homeowners gave their milkmen a house key. This allowed milk carriers to let themselves into the house and deposit the milk in the icebox if the homeowner wasn't home. It was a convenient system built on trust.

The milkman was as reliable as the postal service

There's an old adage about the postman coming rain or shine. The same thing could be said about most milkmen — except many milkmen, unlike their mail-carrying counterparts, did their deliveries seven days a week. (To be fair, some mail is now delivered on Sundays in the U.S., making it a seven-day-a-week proposition, too, though that wasn't always the case.) It's certainly not an exaggeration to say that the milkman walked as much as the average postal worker did during his years of delivering milk, with some milkmen walking around 150,000 miles over the span of a 50-year career, per Wendover News.

It was also the case, in Europe at least, that milkmen had a reputation of not only coming rain or shine, but even when the ravages of war made delivery nearly impossible. As for the reason why those milkmen were so lionhearted, Sarah Wassberg Johnson suggests that it probably had "a lot to do with the perishable nature of milk and the fact that cows produce milk daily," making milk delivery a necessity regardless of what was happening in the world.

World events greatly affected milk production and delivery

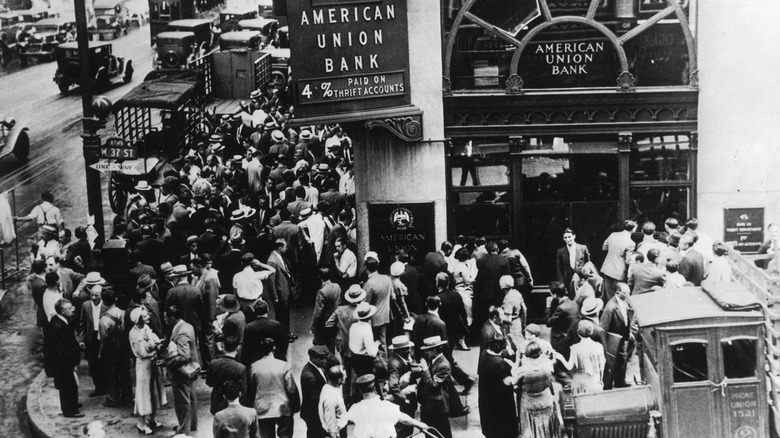

As you might expect, The Great Depression, as well as World Wars I and II, significantly impacted milk production and delivery. Price gouging in the early part of the 20th century led to milk riots and economic hardships for dairy farmers during those years in places like Wisconsin and New York. Grain prices in Europe during World War I also skyrocketed during that era, which bumped up production costs and put even more strain on dairy farmers. Milk farmers didn't fare any better during the 1930s.

The real push to get agriculture — and by extension, the dairy industry — out of the throes of the Great Depression arose from the onset of World War II. Milk production was anything but slow during World War II. The United States' government ask dairy farmers to increase their production levels by 6% to 8%, per Cumberland Times-News.

By 1942, members of the general public had started tightening their belts as wartime rationing restricted their consumption of metal — specifically, tin — and milk, two raw materials the war effort needed to send canned milk to the soldiers overseas. It was also the two World Wars that put more female milk carriers on the streets for a time. Typically, women worked in the creameries, but not as milk carriers until the wars pulled male milk carriers off their routes and onto the front.

Milk delivery could be a hard and dangerous job

Given the cheery portrayal of the milkman in magazines like the Saturday Evening Post, it's no wonder that many people have a nostalgic view of the milk carriers of old. However, reality could be a bit different. For some milkman, the job presented occasional brushes with danger, including attempts at highway robbery.

At least one milkman, Hiram "Ross" Graham, lost his life at the hands of a shooter while he worked his milk delivery route in Florida in 1968. Another long-time milk carrier, Carl Sorenson, reported a robbery attempt while he was on his route during the 1970s.

The milk riots of the early 20th century also set the stage for violence against milk truck drivers. Dairymen groups in New York and Wisconsin instigated milk strikes during the early decades of the 20th century to get better prices for their milk. They reinforced the strikes by dumping milk, pouring kerosine in the milk supplies, and even blockading milk delivery with bayonets and tear gas. All of this made the job uncertain and dangerous during that era.

Industrialization and health scares played big roles

A perfect storm of inventions and events set in motion the decline of the milkman. After World War II ended, rationing ended, too. People wanted to buy stuff, all the food, appliances, and conveniences that wartime austerity measures forced them to do without. Thanks to an abundance of refrigerators big enough to hold everything consumers bought at the supermarket (and no further need for ration cards), they could hoard all the milk they wanted

The average consumer just need to go to the dairy aisle to buy milk and then take a trip around the other aisles find other foodstuffs, like pasta and bread. People no longer had to wait for the milkman to deliver their dairy. It was like having access to the goods of the Black Market during the war, except in the post-war years, hoarding all that stuff was legal.

Additionally, pasteurization killed off many of the most prolific pathogens, like tuberculosis. As a result, people didn't need to get milk daily because pasteurization meant milk didn't go bad as quickly. Working in tandem with this were the new cardboard milk boxes that, unlike glass milk bottles, would only be used once and wouldn't break into a zillion pieces if dropped.

And don't forget the era's explosion in automobile ownership. Having access to their own car ensured that average Americans could go to the supermarket anytime they wanted to. This new era of mass production made milk-drinking safer, easier, and cheaper sans milkman.

Transportation advancements created less need for the milkman

Who among us hasn't been stuck behind one of those giant 8,000-gallon trucks that look like a giant thermos on wheels? The average milkman, even in the biggest of delivery truck, can't compete with this modern marvel of the milk industry. Milk delivery for these thermos trucks begins at the dairy, where it's stored in giant refrigerated containers. It gets a treatment of antibiotics and checked for bacteria before being poured into the giant thermos.

The drivers then deliver the milk to processing plants. Along the way, they regularly inspect the milk for temperature and to see if there is any leftover antibiotic residue. And because the trucks boast enviable amounts of insulation, the milk remains cold and fresh until it gets to the processing plant where it's eventually packaged and made ready for the market.

Sure, it goes back into trucks once it's boxed up, but those trucks are larger than anything the milkman's ever going to drive. And the truck is headed to the grocery store where it'll be unloaded onto shelves in large quantities. It's a way more efficient and cost-effective way to getting milk to consumers than relying on a cadre of old-fashioned milkmen.

The rise of grocery stores in the post-war era impacted milk delivery

Progress always causes casualties, and the milk industry and the milkman of old are just a few examples of this. People forget this because in the 21st century, getting a chilled glass of milk is as simple as heading to the fridge, pouring a glass, and drinking. And when the milk runs out, a trip to the local grocery store replenishes the supply.

The ease with which one procures milk in the modern world creates a bit of amnesia. "Commercial electric refrigeration, the development of coated cardboard cartons, homogenization, and automobiles all had huge impacts on milk production and delivery," Sarah Wassberg Johnson points out.

By the time that the 1950s rolled around, at more than one-third of food came from the grocery store. About 10 years later, give or take, that number jumped to 70%, according to the Progressive Grocer. Thanks to the pandemic, grocery delivery, which probably included a good deal of dairy, jumped back up to 55%, per the United States Department of Agriculture.

There is a certain irony behind this recent trend. Almost immediately after World War II, delivering milk, creamy cottage cheese, and other dairy door-to-door became too expensive to be sustainable. Most milkmen started losing money on their routes due to the longer distances between stops. It was a distance created by suburbanization, cars, and people doing their own shopping.

Once the pandemic hit, economics once again pushed delivery into the forefront. COVID-19 restrictions forced people to stay inside and reduced much of the gadding-about-town business to essential workers only, which included grocery workers and delivery personnel. And because of all of this, the milkman was back in business once again.