How Chicory Became A Major Part Of New Orleans Coffee Culture

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

Coffee culture in New Orleans, Louisiana, can be likened to DNA's double helix. One side of the helix is held in up by coffee, the other by chicory. So intertwined is the blend of coffee and chicory in the city's coffee houses that it's rare to find one in your cup without the other. As Kayla Stavridis Head of Marketing at Barista HQ explains, "The mix of chicory and coffee has endured because it's more than just a necessity; it has become a symbol of NOLA's resilience and resourcefulness."

The resilience that Stavridis references is linked, in part, to when the Port of New Orleans was blockaded during the Civil War and coffee imports nearly came to a screeching halt. People living in NOLA rescued their coffee habit by mixing their java with chicory root. And in extreme cases, when hot coffee disappeared altogether, coffee drinkers replaced coffee with its taste twin, chicory. Today, centuries later, the citizenry of New Orleans hasn't given up this culinary mash-up. According to tour operator for Unique NOLA Tours and self-admitted history buff, Christopher Falvey, "New Orleans is very traditional. It is quite rare for trends to take hold. [...] we generally like our coffee the way we've had it for decades — if not centuries!"

And it took long centuries, indeed, as well as plenty of political, economic, and social changes for NOLA's coffee traditions to take hold. And that includes residents' preference for the special java-and-chicory blend that the city's known for.

French and American politics played a role

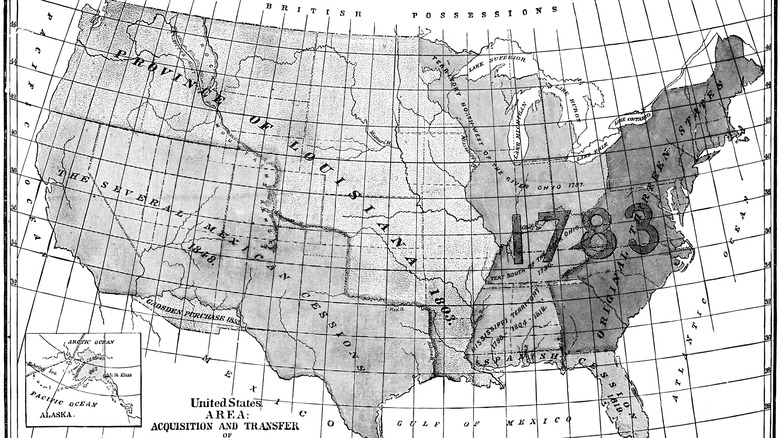

At the turn of the 19th century, French Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte had big plans for the Louisiana Territory (and, specifically, New Orleans) and other French colonies, including Saint Domingue, now present-day Haiti, which would produce crops like coffee and sugar. At the time, no other place on earth produced and exported more coffee than Haiti did. Some 60% of coffee sales in the world were attributed to the country during that time, per Sweet Maria's Coffee Library. In this scenario, one set of French colonies — those in the Caribbean — were to produce goods, including coffee, that would find ready buyers in another colony, Louisiana, and specifically in the port city of New Orleans. But a major event got in the way of Napoleon's plans – the slave revolt in Haiti from 1791 to 1804. which eventually led to the sale of the Louisiana Territory in 1803.

One may wonder why the Napoleon decided to sell the Louisiana Territory to America, given how lucrative the crops in Haiti were. Basically, for the deal to work, Haiti's coffee, sugar, and other imports needed to be in the picture. But the imports ceased after the revolt, and once France lost Haiti, the Louisiana Territory, including New Orleans, held little value for Napoleon. The deal left behind thousands of miles of land, a lucrative sea port, and numerous French settlers, all of which formed the foundation for NOLA to become one of the world's most prominent coffee cities. And it set the stage for chicory to take a stronghold in the city when the right turn of events went down.

Mixing chicory with coffee started during the Napoleonic Wars

In 1806, Napoleon embargoed British trade. No imports that originated in Great Britain would be allowed in French ports. As a result, coffee imports in Europe declined dramatically, and coffee drinkers throughout the continent searched for a viable substitute for coffee. Enter chicory, which became a coffee stand-in for Europeans and an export product that the emperor could send to the New World during the early part of the 19th century.

That didn't mean that chicory sat well with everyone, however. President Andrew Jackson thought that the chicory-for-coffee substitute made for a poor cup of coffee. The president spent a good deal of his time trying to convince the people that they should be drinking coffee instead of chicory, or even a blend of the two. By 1812, Napoleon's attempts to build a Europe that wasn't held together by the morning cup of caffeine failed. There was a silver lining in all of this, however. By that time, chicory had established itself as coffee's twin and in-cup complement in the eyes of the French, both in Europe and abroad in America — a substitute that came in handy once the canons of the Civil War began booming.

An enslaved woman founded coffee culture in New Orleans

Renowned coffee houses that serve chicory coffee, like the Cafe Du Monde, probably wouldn't exist as we know them today, and, indeed, owe a great debt to a formerly enslaved woman named Rose Nicaud, aka Old Rose. She lived in the early 1800s and is credited with starting the first coffee stand in the city and, by extension, establishing the beginnings of coffee culture in the Big Easy.

Originally from Haiti, it is thought that Rose Nicaud's situation in America allowed her to move about town freely, due to a contract she created with the person who enslaved her. With that arrangement, Nicaud set up a weekend coffee stand in the French Market, selling her own special blend of chicory coffee (near where the Cafe Du Monde would exist some 60 years later). The French Market was also in the vicinity of the St. Louis Catholic Church, which gave Rose a ready supply of clients, who were eager to buy her wares after mass let out.

It has been suggested that during her heyday, she made the equivalent of between $1,400 and $1,600 a day in today's dollars, per The Iron Lattice. Eventually, Rose Nicaud earned enough money to buy freedom for herself and her husband by taking advantage of the laws of manumission in Louisiana. And as a fitting end to the story, it's worth mentioning that a couple of hundred years later, she was the inspiration behind a coffee shop which bore her name: the Cafe Rose Nicaud.

Wartime blockades caused coffee to become scarce in New Orleans

If there was any agriculture in the city of New Orleans, it came by boat from the harbor. And commerce was the fertile soil that allowed life to grow up in and around the Big Easy prior to the Civil War. A Union blockade of the Port of New Orleans nearly put a stop to all commerce in the city, including the coffee imports that came into NOLA from the Caribbean, the Americas, and Cuba. No harbor access for the boats carrying coffee and other imports meant little to no caffeinated beverages for the Big Easy (and beyond) during the war.

The solution for residents of New Orleans was to try to extend the coffee that they already had. For those of French ancestry, chicory was the obvious solution. They knew from experience that roasted chicory root had a similar taste and mouthfeel to coffee. But it brought more to the table than that. As Kayla Stavridis points out, "Chicory adds a distinctive taste — slightly earthy, nutty, and sometimes described as a bit "woody" — unique to NOLA's blend."

If anything, the pairing of coffee and chicory augmented the flavor of coffee instead of detracting from it as so many of the other wartime fillers did. In other words, residents of New Orleans didn't necessarily feel like they were doing without coffee when they drank the blend. What's more, chicory could be grown locally, making the city's inhabitants less vulnerable to the vagaries of war and the issues it caused in the coffee supply chain.

Cafe Du Monde was established during the war

Every day, every hour of the day, without exception, (well, besides Christmas), the Cafe Du Monde in New Orleans pumps out two things it has become known for: a triple serving of square-shaped French donuts called beignets and steaming cups of cafe au lait coffee made with a mix of coffee and chicory root. Cafe Du Monde has existed for more than 160 years, and for most of its life as a restaurant, it has served its coffee-chicory blend.

There's a reason this NOLA eatery is so famous, aside from the fact that it's the city's oldest. It came to life in 1862 during the second year of the Civil War. Moreover, it has managed to survive the ravages of war and the myriad hurricanes that have swept through the city since its inception more than a century and a half ago.

And while modern coffee culture in the city does occasionally indulge the taste buds of those who love flavored coffee drinks that taste like Hershey bars, the Cafe Du Monde remains true to its roots. It's the place to go in the city to find the kind of café au lait that would have been served during the Civil War –- that is coffee with an equal mix of both coffee and chicory with a little milk to color it golden brown.

Soldiers suffered due to the lack of coffee

While the Union blockade of the Port of New Orleans immediately affected those living in the Big Easy, the effects of it hit those living beyond the city's borders, too. The troops on both sides of the conflict felt the effects of blockade-related coffee shortages. However, the situation in the North was mitigated when President Lincoln found a new coffee supply in Liberia which he could ship through other American ports outside of Louisiana.

The people in the South, including the soldiers of the Confederacy, weren't so lucky. For a time, soldiers in the South still received their coffee rations, but by 1863, coffee supplies for Southern soldiers had dried up. According to American Battlefield Trust, one soldier laid out the coffee situation plainly in his journal by saying, "We are reduced to quarter rations and no coffee. And nobody can soldier without coffee."

The situation got so bad that soldiers went to great lengths to get their coffee. Like those living in New Orleans did, soldiers stretched the coffee rations they had with any number of things, including okra seeds, corn meal, cotton seed, rye, parched wheat, sweet potato, and of course, chicory. However, even stretching coffee with chicory wasn't enough for some. Some Confederate soldiers took to scouring former Union campsites to see if there were any leftover coffee beans to be found.

New Orleans still plays a critical role in modern coffee culture

"New Orleans has a coffee culture that is unlike any other," says Kayla Stavridis. Certainly, the amount of coffee that comes through this great coffee city makes this so. Within the last decade or so, it hasn't been unusual for 250,000 tons of coffee to come through New Orleans in a single year. That's enough beans to make 20 billion cups of coffee.

However, coffee culture in the city still hasn't forgotten its roots. The mid-morning coffee break, where people break up their workday to catch up with friends over coffee to chat, began in the Big Easy in the 1920s. Stavridis elaborates on the spirit that set the stage for this in New Orleans. "Coffee shops in NOLA are about community, hospitality, and taking things slow — sitting down with a cup of café au lait (often made with the famous chicory blend) at a local café is more than just a caffeine fix; it's part of the city's social fabric."

Vietnamese coffee, with its strong flavors and French influence, has found a home here, too, along with the immigrants who have opened Vietnamese coffee shops in the city. Many of them pay homage to their adopted city by mixing their already-strong coffee with chicory as is the way in NOLA. This is probably inevitable, given the history of the caffeine-free coffee substitute in the Big Easy. As Christopher Falvey points out, "People in New Orleans love strong tastes. [...] So when it comes to coffee, we love it very, very strong. The chicory does this."