Alton Brown Has A 'Perfect Problem' With Martha Stewart - Exclusive Interview

In today's media age, you can enter any restaurant, throw a spoon, and hit 50 influencers. Doing so could probably even turn you into an influencer. That reality makes it hard to remember a time when food media was novel. Or, at least a time when smartphone cameras weren't a lurking presence at every table.

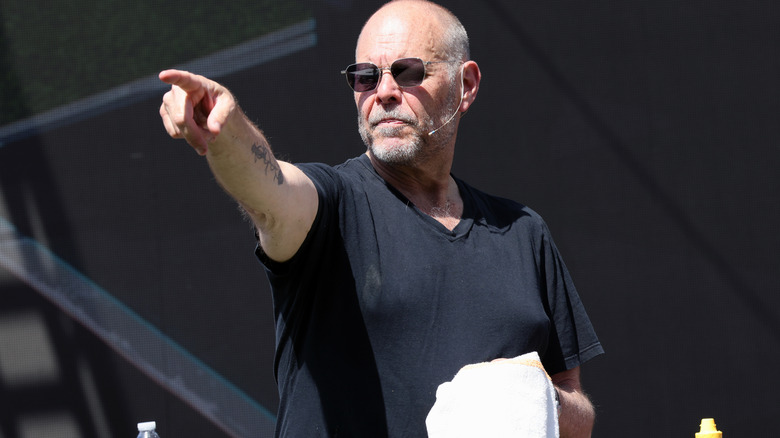

Cynicism aside, to cook something is to change it. Food media has been changing since the moment humans first broadcast it. Few people have as intimate a view of that change as Alton Brown. His career as an author, television man, and live demo food scientist has been symbiotic with the growth of food media over the past three decades. Now, the arch of information technology is bending toward artificial intelligence, but Brown, who prefers to think of himself as a "really groovy home ec teacher," has decided there are a few more lessons he'd like to teach.

"Food for Thought: Essays and Ruminations" is Brown's new book. Dropping in February, it joins a live experience called "The Last Bite," a culinary variety show that Brown will tour across the country in 2025. The name isn't just symbolic; Brown expects this to be the final installment of a program that he's been doing on and off since 2013. Ahead of his big year, Chowhound caught up with Brown to discuss what attendees can expect, and what curious readers should know about his book.

The Last Bite is Brown's last tour

What can guests expect from this, being your final tour?

Like the three tours before, a culinary variety show, which I'd like to think is an entertainment form I invented. I'm not 100% sure. Very much inspired by the variety TV shows of the '70s, Sunny and Cher, things like that. I've always loved that form where there's some spectacle, some comedy, some music, a mixed bag.

This particular show is kind of different from the shows that we've done before ... a lot more immersive storytelling using some technology that we haven't used before. There is a general theme that the show takes, and I will give away the fact that there's going to be quite a bit about steam in this show. We usually do at least one really, really, really large, really bizarre food demonstration where we build a large device that cooks something. This time we've made something that's about three times bigger than anything we've ever done. We even had to turn down some theaters because the stage wasn't big enough for the demo.

There's not going to be quite as much music this time as there has been in the past, simply because we've got so much else to do. There's still a lot of audience interaction. There's going to be a lot of volunteer work up on the stage, and there's even a competition near the end of the show that I think is going to be a lot of fun.

Is there a particular reason for using steam? Were there moments during the planning process where you thought this would be just a great centerpiece for this theme?

There's a personal thing going on here for me, which is that in the last few years I've gotten to a place in my career where I was trying to look at where were the holes in my culinary education. I realized a few years ago that my black hole is a proper understanding of the actual base concept of being a cook, which is heat. To really get cooking, it really, really helps to understand heat. I didn't. I didn't realize that I didn't. Then, when I did realize that, I plunged myself into a year-long study of thermodynamics ... It's human beings ability to apply heat to food that makes us cooks. It's allowed us to become the masters of the planet because we've been able to make our food safe, we've been able to free up nutrients. That all has to do with heat.

When I was making "Good Eats," especially in the early 2000s, so many of us were struggling to teach cooking through a television or through a passive media. Instead of standing next to someone saying, "feel this, do this," we all just started talking about the temperature of things. We created a misunderstanding that temperature is the same thing as heat and it's not. Although interrelated, they're not the same thing.

The show that I'm doing, "The Last Bite," is a long love letter to heat. One of the greatest expressions of heat in the modern age has been steam, which is the only cooking environment that can also be used to power massive machinery. That makes it interesting ... We have built a device that uses steam power to also cook something. A very popular American food that would not have existed were it not for the Industrial Revolution. I'll leave it at that. That all sounds very academic, but trust me, it's actually a lot of fun.

Sometimes the volunteers get a little too involved

As you look back on this being your final large-scale tour, have you had any particular moments or experiments where things went awry on stage or with volunteers? Were there any memorable moments where they went way better than expected?

When you're coming up with a live show like this, having things go wrong is just going to happen. Something's going to break. But if you plan for those things, they generally can be circumvented. It's like if there's suddenly a detour because some electrical part goes bad or something happens ... If you're smart, you want to survive on the road, you build in a plan B. Everything has to have a plan B.

There was a night during my second tour, "Eat Your Science," where I blacked out on stage from sucking too much helium that was being used in a demonstration. I only blacked out for a second and I never actually hit the floor. Things like that. I've been burned. Things happen where after the show you're like, "ah, crap, I sure wish that hadn't happened." Nine times out of 10 the audience doesn't know.

However, when you're dealing with volunteers on stage, especially in a theater that has a bar, interesting things can happen. We build a lot of stuff for these shows, so that when people come up on stage, they're not just like grist for the mill. They're very much in the driver's seat of seeing which way the show's going to go. Usually, it's absolutely delightful. People are generally very excited and they make the show a lot more fun and interesting for those of us that have to do it every night. Every now and then somebody will have perhaps more alcohol, be a little over-served.

I remember one night, I'm not going to say what city it was, but it was a show in California ... I had a volunteer on stage who was somebody's grandmother. Very nice, very kind of proper looking lady in her probably later 60s, who had some drinks and could not keep her hand off my ass. Which is funny for a little while. Then, you start thinking about, holy crap, what are we going to do? We've got to make it through the show. Times like that are few and far between.

Unlike a play or some big musical ... the show is different every night and it changes depending on the house and it changes depending on the crowd. Thursday night ain't Friday night. You've got to embrace that. The thing that I enjoy the most is that the show is a template. Every good show of course is a very tight template, but it's got to have room for that audience involvement.

How Brown thinks Good Eats fans have grown over the years

Throughout the years that you've been doing this and engaging and involving the audience in such a way, have you seen a big change in the way they approach their culinary skill or their scientific interest or just the evolution of the people who followed you?

Well, I'm not going to say "all," but a great many of the people that come to my shows were fans of "Good Eats." Some of them grew up on it. Some of them — I was like literally Mr. Rogers to them ... They'll remember things. They'll say lines to me and I'm looking at them like, "well, I know that's probably from a 'Good Eats' episode." I haven't actually memorized these in a long time.

They're always super smart, they're always super engaged and they tend to be extremely passionate about cooking. I just kind of take that as ... that's just going to be the accepted thing. There are occasionally people that will come because they're being dragged by someone who was a fan of the show, but they themselves don't know it. They'll be like, "I don't know what this was going to be about, but hey, we had an awful good time."

That's one of the things I want to make sure of. Even if you're not a cooking fan, even if you don't know me from Adam, you'll still enjoy the show. Lots of times, especially in places like Florida, what will happen is that we'll be sold as part of a Broadway series. Season ticket holders, some of which have never heard of me before, ever in life, will come because it's included in their season tickets. They'll fill the first two rows. So the people that are closest to me will have no idea who I am whatsoever. So I have to work really hard to engage them. [They're] looking at me like, "What? We thought you were going to cook some eggs or something." Which I am doing in this show. I am cooking today. So that always keeps you on your toes.

By and large, the audience is someone coming in with their young family, and they themselves started watching "Good Eats" like 25 years ago or whatever. They've lived most of their life with the stuff that I've made. They tend to, in the best case, use "Good Eats" to springboard off into studying other parts of cooking for themselves. In a lot of cases, they know a lot more than I do, which is great.

Alton Brown thinks the way we taste food is changing, too

That makes me think about the essay "Hunt and Gather" from your book, which talks a lot about the evolution of how we see food in a social media world. Beyond the literal aspect of social media existing and being used to see food and people cooking, how have you seen the act of culinary discovery and exploration change?

Well, I certainly have seen change and any of us that have been paying attention have seen change. People are certainly more food-centric, more aware of different foods and different ingredients and different cultures. At the same time, I noticed that people have forgotten completely how to describe what anything tastes like.

I'm not sure that we're tasting with our mouths and our noses and our chemical senses as much as we used to. We're mostly tasting with our eyes. We're looking at it on Instagram, and we're interested in what it looks like and we're interested in the imagery almost as though it's iconography. I can look at Russian religious icons from the 13th century, but also feel nothing. I think that we have fractured our food input in such a way that it is so heavily leaning on the visual that we don't really know what it smells and tastes like anymore.

I'll sometimes ask people, especially younger people, "Tell me about your favorite dish. Now tell me what it tastes like. Describe it to me." They have a very difficult time doing so. They have a very, very difficult time talking about how they feel when they eat it or smell it. Especially our olfactory sense is connect directly to our limbic system, they're almost two sides of the same coin.

What you should get is a flood of emotion ... In certain cases, it's the "Ratatouille" moment where all of a sudden you take a bite of food and it's a spring day when you were six and your mom's giving you a hug. Or you take a bite of caviar and suddenly you're in the back seat having your first make out session when you were in high school. Something that is the mystery of what we think and what we feel and what we remember and what we associate with food.

Now, it's just a bunch of pictures, which as I talk about, is kind of like pornography. Pornography really doesn't have that much to do with sex and Instagram food pictures don't really have anything to do with cooking or eating. We've done that because we adapt to technology. Very few people develop technology and then the rest of us adapt to it. Who am I to say that's a bad thing? I just have seen it. I've noticed it, and I think it's sad. I think it's sad because I think we look without thinking. We don't feel the food in our mouths or in our hands much anymore. We don't taste like we used to taste. We'll say something's delicious. Okay, great, but there's so much more and there should be.

The AI effect on food

This has crossover with your essay "AI and the Asparagus," which is about AI-generated recipes. There is a build-up of fake, AI restaurant profiles on social media. You look at these dishes and maybe some of them look fake and maybe some of them look real. How do you feel about this?

You know what? If you're pulling off a pranky kind of thing, like we've stuffed a cow into a giant squid kind of thing, where it's clearly not real and is therefore in the realm of absurdist or surreal art — that's one thing. When we lose the ability to actually know, then that's a really weird place to be.

It's fascinating. We need to look at where we are and how we got here with our attitudes and our opinions. Only then can we start to understand where we're going. I've noticed the thing about the fake profiles, and I'm always kind of like, all right, well wait a second. It's a real profile but for a fake restaurant. Does that even matter anymore to anybody? I don't know if it matters to anybody anymore. Do you know?

No, I don't. During COVID, ghost kitchens and things popping up on meal delivery apps really asked the question, "what is a restaurant?" What does it look like in this environment and this economy, and how does it change in size and scope?

I was going to write an essay on this. It kind of got left out because I don't have it fully formed yet. I think that ultimately it will be valid to create a restaurant that does not serve food. I think that when you start creating imagined spaces, whether it's AI, whatever it is, people will dwell. Let me look at video games. Is "Grand Theft Auto" driving a real car?

No.

Okay. It isn't. You're not actually going anywhere. You're not actually driving a car. At what point can we reduce food to such a visual thing ... My wife is a professional restaurant designer. We've had the conversation, and I think people would pay to have access to a beautiful design space that is virtual and a menu that is virtual with photographs of food that are virtual.

So much of the experience is no longer the eating of the food or the touching of the food. As long as you let only a certain number of people into that space at any given time, people will probably want to go there just to look. If we're going to reduce food to the visual — and design is so important — why does it have to be in a real place? Why do you actually have to eat anything? Or at the very most, you get a recipe for a dish that doesn't exist, from a restaurant that doesn't exist. I'm not sure that's farfetched.

It makes me think of folks who like dining for the simple aspect of being in a place, being seen, and maybe will order and not even really eat their food.

It just seems to me to be a natural extension. I mean, if you draw the line from where we've been to where we are, and then just draw it out straight into a hypothetical future, I think that's where it lands. I know people that go to restaurants, especially in New York, who order food they don't want, made with ingredients they don't like, so they can take a picture of it and say that they had it. It's a free country.

Alton Brown has been exploring English cuisine

One essay that I found fascinating was "Origin Story." You're writing about finding out your ancestry and learning English cooking. What's your study of English cuisine been like? Do you have any cookbooks that have become absolutely necessary?

Gosh, yes. When you realize that you're the boring white guy and you're not anything but the boring white guy, you have to say, "okay, how am I going to embrace this?" I used to look at traditional British cooking the way that everybody looks at traditional British cooking. Never thought of it as mine. Taking that almost anthropological look has sent me back. I'm starting as far back as I can, at least as far as going on a few hundred years, to Hannah Glasse and then moving up into Mrs. Beeton, and stuff like that. I'm learning. It's not that I'm learning that much about food per se. What's so difficult is that we can't get the ingredients. We can't get these foods anymore. A pheasant that was shot and hung up to age for a month. There is nothing that tastes like that unless you do it.

One of the things I'm hoping to do is to take some time after this tour's over to see if I can actually get some of these things. The fascinating thing of course, moving into the Victorian period and on, is where you start seeing homes not having servants. The wife is now doing this cooking. It is being internalized into the home and ownership of the food is being taken by the people in the family. That's a really fascinating thing to see happen and the way that it affects how recipes are written.

There weren't many recipes. When the English middle class, at least in the cities, had servants, that information stayed within the servant circle. It's not like anybody else in the household was keeping serious records and knew what was being done with the food. What they knew was what food they were getting receipts for. Of course, receipt and recipe have the same root. It comes from the same thing. It was a list of things.

We can get the household ledgers, and see what was bought and what was spent for it, but don't often know where it went or how it was used. It's only the late 19th century where you start seeing real household recipes the way that we think of them. Because I'm an English language speaker, what I have found myself dealing with is really the evolution of the recipe itself as a form, more than the food itself. That's going to take a little longer for me simply because I don't have access to the ingredients that are so often called for in these kind of historic British situations.

What's interesting also is to see what came in from other lands. That's one of the things that I talk about in that essay, which is that we are talking about the original colonialism ... We see curries and things coming into and from this country. How they're adapted is really interesting and something that you do not see in any other European cuisine other than the Spanish, but that's from much, much earlier. You don't see that in German cuisine. You don't see it in French cuisine or Swiss or Russian, which is another ... Western Russian cuisine as a European cuisine is also super fascinating. It's opened my eyes a lot and I hope to spend a lot more time on it.

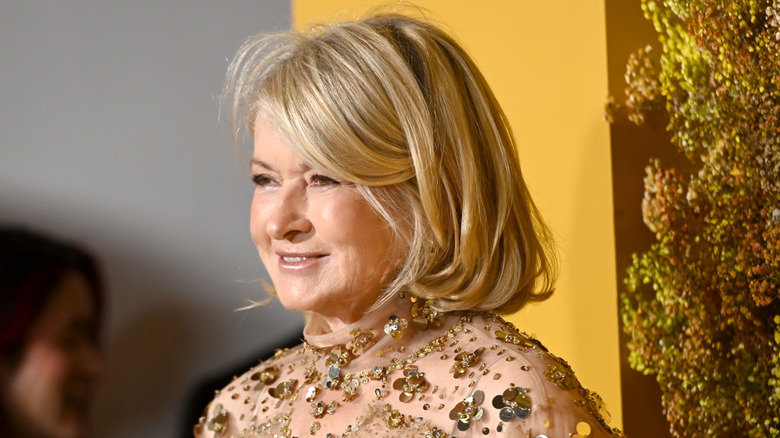

Brown's hot take on Martha Stewart

I have to ask about the "Perfect Problem," an essay about how you feel Martha Stewart has made homemaking and hosting inaccessible.

My one instance of true b******g in the entire book.

I'm sorry, I had to ask.

It comes out of the fact that all the things that I said are true. People used to actually enjoy entertaining and enjoyed having people over and didn't fuss the way that they do now. That age is gone. It vanished. I watched it happen. This is before I was even in this space. Before I went off to culinary school. I saw this happening and saw the phenomenon of this desire to be perfect rather than to be yourself. This general sense of not being good enough to entertain and not being perfect enough, not having the right things, not serving the right foods, not having the right gravel in your driveway, whatever it is, is something that I find repugnant. I hate it. When my wife and I entertain, we entertain so simply. It's like people seem a little taken aback by the fact that we'll not be perfect. We use chipped plates. The chicken might be a little overdone. This is our life.

When COVID hit, my wife Elizabeth and I started doing a YouTube show called "Quarantine Kitchen." One night she said, "You ought to do some un-produced content." I just turned on the computer and we went live ... We never used anything but two lights and a phone, and we never shopped. We never planned. We just drank and cooked whatever the hell it is we had. We showed off everything that was screwed up about our life. We showed this mess of a pantry. We had pantry moths at the time that we couldn't get rid of. The refrigerator was always a mess. There were dirty dishes in the kitchen, and people went freaking nuts ...

It was then that I started thinking back about these friends that I had known, especially in the late '90s, early 2000s, that had stopped entertaining because of the Martha Stewart books and Martha Stewart in the media. I started seeing the lines of connectivity between these issues. Between the fact that we were getting all this organic love really by being so utterly imperfect. By being willing to share that imperfection, by saying, "Crap, look at this. Holy hell, how did that happen?" It happens to everybody who's living a normal, mortal life on planet earth.

Now, if you aspire to the level of perfection that she clearly lives in, great. Then nothing I say is going to put you off of that. I feel strongly about it. I've never met her. I don't know her. She might be the best person on earth. She's interesting because she's been to prison, and that makes her kind of interesting just right there. She's fabulously rich and she's written 99 freaking books. I mean, oh my God. It's clearly resonating with somebody, but I think there's a downside to it. I think that downside is authenticity.

On a personal level, I always find that it's sort of "perfect is the enemy of the good" when entertaining.

Perfect is also the enemy of the authentic. It's so strange that when we are online, when we're in social media, we use this word authenticity all the time ... Sharing your own authenticity is a risky and scary thing because it can mean rejection. We don't like rejection, but if we're going to have these authentic relationships and we're going to share our food and our table and our alcohol and all these things, we need to embrace that.

The only fast food Alton Brown would break for

You've written that you never eat fast food anymore. Is there a restaurant or chain that would or could be the exception?

It won't be an exception, but I think that if I was going to feel the pull, the magnet pull, it'd probably be Arby's. Those Arby's roast beef sandwiches are freaking magical ... It's funny because the last time that I had one, and I mean it's been a while, it tasted exactly like I remembered it tasting from childhood. Whereas every other fast food tastes different to me than from my childhood. I cannot have McDonald's in my mouth because ... Everything tastes like it's made out of sugar. Everything's sweet to me. I have great memories of McDonald's.

When I was a kid in California, it was kind of like every two weeks we got to go and I got to have one little hamburger at McDonald's. That stuff doesn't taste the same anymore. Chick-fil-A no longer tastes ... I live in the South, so Chick-fil-A is a thing. I broke up with them when they stopped making slaw. So I can't talk about it, but I'm still not over it. I love their slaw. Arby's, last time I had one, still tasted like Arby's.

"Food for Thought: Essays and Ruminations" is available on February 4, 2025, preorder it here. Tickets for Alton Brown's final tour, "The Last Bite," are on sale now.