How Fake Whiskey Took Over The Market After The Civil War

These days, whiskey in the United States is regulated pretty strictly. For what you could argue is the United States' flagship spirit, bourbon must abide by rigid rules, including controlling what bourbon is made of to begin with. Further still, some bourbons are bottled-in-bond, meaning they follow an even stricter regimen of regulations. All of this is done to ensure a quality of standard in the bourbon business, and, in the case of bottled-in-bond spirits, is the U.S. government's own assurance that you're truly getting what you're paying for. But whiskey production in America was not always so neatly organized. In fact, you only need to look back to the Civil War era to find bourbons that hardly (if at all) fit the bill of the spirit.

While true bourbon certainly existed in a recognizable way in the years following the Civil War, it only made up a fraction of what was on the "whiskey" market. Supposedly, only a minuscule 10% of spirits under the label of whiskey at the time were authentic bourbons, with much of the remaining 90% being a hodgepodge of neutral grain spirits that would leave their respective distilleries to be flavored, colored, and likely watered down by various "rectifiers," before finally making it to any number of saloons or similar establishments via a wholesaler. So while whiskey distillers today like to evoke that romantic bygone time of untamed whiskey production, whiskeys of the time were a far cry from the spirits we have now.

What conditions led to all this fake whiskey?

Naturally, having an absolute flood of fake whiskey in the country isn't something that just crops up overnight, and there are a few factors that led to inauthentic whiskey taking over the market in the years during and following the Civil War. First and foremost, there simply wasn't much legislation in place describing and enforcing the authenticity of bourbon. It's clear now that bourbon must be made with at least 51% corn, but such regulations were either lax or nonexistent throughout the country. Thus, it wasn't uncommon to see a "bourbon" made from distilled molasses, or a "bourbon" that was really just another distilled grain spirit, usually of concerning potency. These experimental recipes and additives gave whiskey of the time several dubious nicknames, including "rotgut," "coffin varnish," and "strychnine," among others.

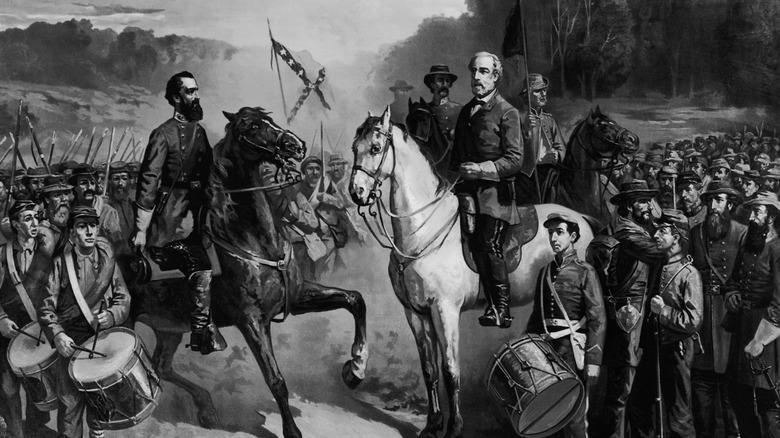

Another thing to bear in mind is the considerable black market for whiskey, especially in the southern states, in the Civil War period. The Confederacy enacted what is essentially proto-prohibition, banning the production and consumption of liquor. During the Civil War, this was enacted with the justification that grain was needed for food, and that the copper comprising the still was needed for brass war goods like cannons and even uniform buttons. Unfortunately for these states, though, this drove the whiskey black market into a frenzy, leading to the production of spirits of extremely questionable quality.

Bringing bourbon back on track

If you're curious about what these spirits might have tasted like, then you're unfortunately out of luck for a couple of reasons. The first is that whiskey back then was simply unreliable -– it was hard to tell what you were getting from one bottle to the next. So narrowing down a flavor profile beyond "ethanol" for these often-very-strong spirits is difficult. You can say that these fake whiskeys were wickedly potent, made from some kind of distilled grain, and were probably flavored and colored with burnt sugars, fruit juice, and/or glycerin; but that's about as good as it's going to get.

The second reason is that, thankfully, country-wide laws are now in place that regulate whiskey production. Back in 1906, Theodore Roosevelt's administration passed the Pure Food and Drug Act, which brought regulations into the production of American whiskey partially as a means to combat greedy distillers who shilled subpar or outright questionable whiskey to make more money. A few years prior, though, this shift toward guaranteed quality was already taking place, as the Bottled-in-Bond Act passed in 1897, making the federal government the legitimizer of a bottle bearing the B.O.B. label. Even Ulysses S. Grant's favorite whiskey wasn't exempt from these laws, but a bottle such as his preferred Old Crow might still be a worthwhile window into the conflicted past of American whiskey production.