The Origin Of Donuts And How They Got So Popular

For donut lovers, the only invention that's possibly better than the donut itself is the numerous donut maps that have sprung up over the years, allowing said donut lovers to hook themselves up with their current best-loved donut flavor du jour. These maps not only attest to the pastry's continuing popularity over the years but also occasionally mark the origin story of new donut types — like the cronut, that fried croissant-donut hybrid — as they make their way into the collective psyche.

The truth of the matter is that donuts, in some form, have existed since antiquity. Donut eaters of old didn't always call them "donuts," but a cross-check comparison of past and present ingredients reveals some consistent findings. That is, people have always loved a good bread recipe that's fried in fat and covered in sweetness, whether it be honey or sugar, regardless of whether the treat comes from a modern cookbook or the unearthed frescoes of Pompeii. The sweet and sometimes savory goodness of these recipes has filled tummies both in the trenches of war and during the greatest celebrations society has ever known, and because of the donut's long history and unparalleled comfort food factor, it can't help being one of the most popular and long-lived foods on the planet.

The earliest donut shops were in ancient Greece and Rome

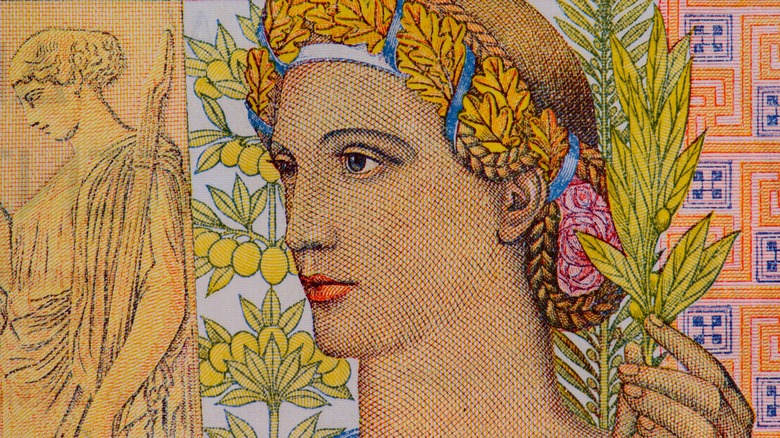

As far as donuts and food history go, the sweet bits of fried bread with the hole in the middle have a long, very storied, sometimes tragic history that goes all the way back to ancient Greece and Rome. When Mount Vesuvius rumbled and belched on August 24th in A.D. 79, it's unlikely that the ancient Romans, standing at the local bakeries, enjoying sweet honey cakes (one of the donuts' precursors), imagined that those chewy morsels would be their last meals. It's impossible to know how many Pompeiians might have been eating honey cakes that day. What is known is that cakes and breads were part of daily life. The remnants of ancient ovens, with chimneys jutting skyward, as well as frescoes of honey cakes reveal the prominence of baked goods in the ancient world.

However, the ancient Romans didn't have the monopoly on honey cakes. The Greeks ate bits of yeasty bread, called Loukoumades, — a version of honey cakes — too. Athletes of today get gold medals. Ancient Greek Olympians got Loukoumades, or "honey tokens" as prizes. And while restaurants, as they're known today, didn't exist, the ancient Greeks of a certain class embraced public dining. Barley cakes were among the items served in these meals, which often wore dollops of honey and clusters of fruit to sweeten them, making them a type of honey cake, or early donut, very loosely speaking.

Donuts appeased both the gods of old and maritime sailors

Unlike in movies like "Clash of the Titans," where the only sacrifices worthy of gods and titans were pure young ladies, in real life, all it took to appease the powers that be in the ancient world were a few donuts. Granted, the ancient world was still in the honey cakes-as-donuts era, but still, the Greek gods apparently demanded food offerings from mankind for Demeter to keep crops growing and, Dionysius, the wine flowing.

Appeasement activities didn't end there. When the ferocious snake that was thought to defend Athens against invasion refused his portion of honey cake, Athenians felt certain that Athena herself must have yanked away the protective forces that would have prevented the second Persian invasion of Greece, helmed by Xerxes and his fleet, from decimating their shores. As far as other parts of the ancient world are concerned, Ramses II in Egypt liked honey cakes so much that they were painted on his tomb walls.

The jury's still out if later seafarers made out better than the Athenians or Egyptians did with their donut offerings. The sailors who worked 19th-century whaling ships earned a fat plate of donuts for every thousand barrels of whale oil they produced, though they were on the savory side as far as donuts go. The donuts were cooked in whale oil, giving them a distinctly fishy scent, but the little nuggets of fishy fat apparently appeased them enough to keep on keeping on.

A 600-year-old donut recipe survives from King Richard II's chef

If you were to read "The Forme of Cury," a 600-year-old cookbook created by King Richard II's chefs, you'd find an early recipe for donuts. Conspicuously absent from this scrawled account are niceties like oven temperature, the addition of water as an ingredient in key places, and, for the modern reader, an understandable version of the English language. But what it lacks in instructions, it makes up for in intrigue. "The Forme of Cury" first saw publication in the late 1700s, and for those who can read its pages, the stories it tells reveal the history of foods as they traveled from Arabic chefs to Portuguese chefs and eventually to the king's table.

The donut recipe itself kinda proves that at least someone at court would have probably been a modern-day Dunkin' Donutter. The king's love of food, pomp, and parties, upwards of tens of thousands of pounds a pop, probably made eating donuts with Richard a real romp. The recipe itself starts with crushed almonds, mixed with rice, and old-English-reading magic to create an early version of donut holes. "The Forme of Cury," which means "A Method of Cooking" in modern English, lives at the New York Public Library and is the library's oldest English-language book in its collection.

Who brought donuts to the New World is contested

If you wish to start a spirited debate among donut-loving food history buffs, just ask them who exactly brought donuts to the New World. The Dutch contribution to the Great Donut Race came in the form of olykoek or oliebollen, or in English, oily cakes. Those little round nuggets of fried dough filled with dried fruit and seasonings first appeared in a Dutch recipe book in 1667. When the Dutch set sail for the US, they grabbed their cookbooks and their love of oily cakes and eventually landed in New York City, which at that time, still went by the moniker New Amsterdam. Among those Dutch immigrants was Anna Joralemon, who opened the city's first donut shop in 1673.

Not to be edged out by their European neighbors, German settlers in the U.S. held fast to a tradition called "fastnachts," which called for them to — oh, darn — use up all their butter and sugar and anything else tasty in the weeks before Lent. They obliged by making a version of donuts to rid themselves of ingredients that might make them do sinful things during Lent, like break their fasts. Fortunately for donut eaters, those fastnachts recipes also crossed the pond with the Germans when they came to the U.S. Unlike the Dutch version, the German version of the treat contained no dried fruit. With just milk, sugar, flour, and eggs, mostly, their fastnachts donuts were closer to today's donuts.

They weren't called donuts until the late 1700s

Not to be outdone by the other contenders for first name rights, Britain put its own version of the donut into the proverbial ring. From the British, the sweet fried bread treats commandeered the donut name. A recipe calling for "dough the size of a walnut," according to the book "The Donut: History, Recipes, and Lore from Boston to Berlin" by Michael Krondl cropped up in Britain around 1750.

If that tale doesn't strike you as a good explanation for the name "donut," well, it turns out there's a related story for that in the annals of food history that you may like better. Donut legend has it that Hanson Gregory, a sea captain in the 19th century, used to bring snacks along on his voyages. Created by his mother, Elizabeth Gregory, these morsels of deep-fried dough included portions of walnuts or hazelnuts in the center of the concoction. While this certainly didn't hurt the taste, the real reason behind such a practice apparently came down to filling up the center of the treat so that it wasn't doughy inside. Literally, dough filled with nuts became donuts.

The first donut recipes in American cookbooks appeared in 1805

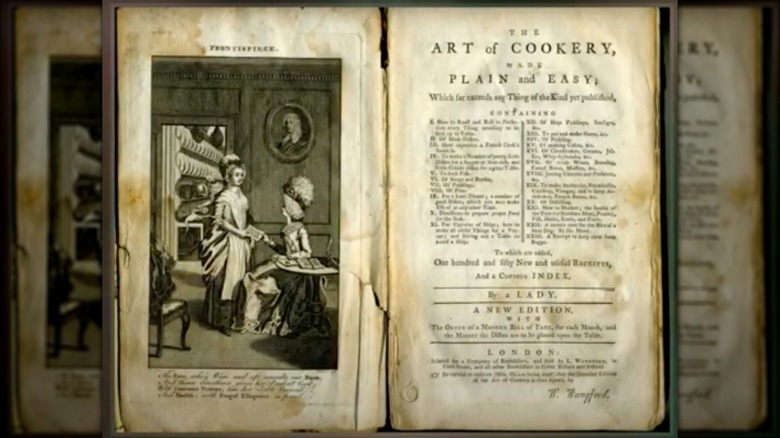

While donuts have had street cred in America since the late 1600s, they didn't earn a mention in any stateside cookbooks until the 1805 edition of Hannah Glass's book "The Art of Cookery" was published. Other incarnations of the book existed prior to this publication, but the 1805 edition included American recipes for the first time.

In all, 20 editions of the book came to print during the 19th century, making it among the most successful of that era. Despite evidence that the word "doughnut" came into the lexicon far earlier, some food historians believe that Glass' book is the first mention of the word. That confusion and the fact that Glass eventually filed for bankruptcy, despite her success as a cookbook author, doesn't detract from the accomplishment. Like Noah Webster's American English dictionary, Hannah Glass' book's first printed mention of the word "donut" contributed to the conversation around and the enjoyment of this ubiquitous treat.

The origins of donuts are tied to Mardi Gras

Probably most people know about the doll-filled king cakes of Mardi Gras, but it's also likely that fewer people know that some wicked donut recipes also contribute to the celebration's sugar high. Since medieval times, Europeans have emptied their cupboards of indulgent ingredients, like lard and sugar, to prepare for Lent. Rather than tossing them, the ingredients became donuts to be enjoyed on Shrove or Fat Tuesday.

Different European countries contributed their own Mardi Gras donut recipes. From Poland came the paczki, a donut that keeps its center intact and fills it with fruit instead of holey air. The Portuguese contributed malasadas, triangle-shaped pieces of fried dough covered with powdered sugar, that became popular in the US after an influx of Portuguese workers came to Hawaii in the 1800s. From the French came beignets. The Germans offered both fastnachts and Berliners, jelly-stuffed puffs of pastry that are similar to the Polish paczki.

It's also worth noting that some enterprising bakers around the country have taken the sweet treats of the Mardi Gras celebration one step further by mashing up donuts and the king Ccake. But no matter what form these morsels come in, few can argue they're a delish way to clean out the cupboards before Lent's season of austerity begins.

The first donut machine increased production and popularity

On the outside looking in, donuts made by machine don't sound quite as appealing as donuts made from scratch, until you think about possibly making several hundred of them in a day, and then a donut machine sounds simply delicious. That's the predicament Adolph Levitt found himself in when soldiers, known as "doughboys," converged on his shop after they came home from Europe after WWI. The donut-lovin' ex-soldiers developed a taste for the holey treats after Helen Purviance and Margaret Sheldon, American Salvation Army Officers, hand-delivered donuts to the trenches to help keep up troop morale.

Once home, the doughboys looked to purveyors of donuts like Levitt to supply them with one of the few comforts that the war had to offer. Given that the Harlem, New York, bakery owner didn't have a particular fondness for forming doughy O-ring after O-ring with his bare hands, he put his thinking cap on and eventually fashioned a machine that made the donuts. The machine plopped raw donuts into a cauldron of oil to be cooked. This created such a change in Levitt's business that he eventually formed the Doughnut Corporation of America, which allowed other would-be bakery and donut shop owners to buy the machine for their own shops.

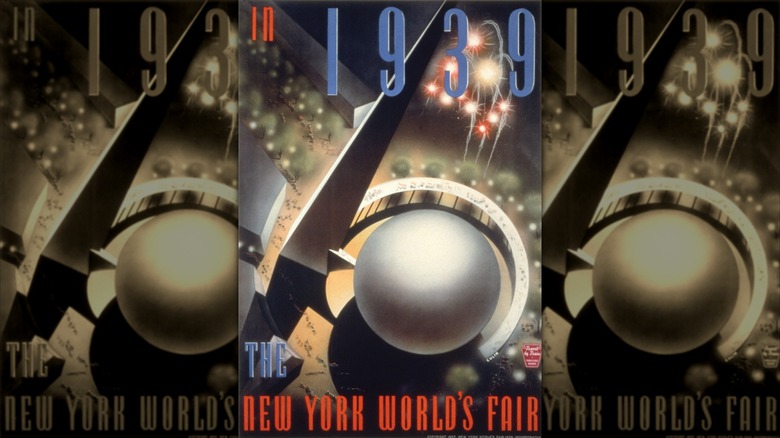

Donuts and coffee became a thing at the 1939 World's Fair

In a world where donuts practically percolate out of the coffee machine at Dunkin', it's hard to imagine a time when seeing these two commodities together represented the best new ideas for the future. But in 1939 at the World's Fair in New York coffee and its partner in crime, the donut, had the shiny newness of robots and View Masters. The powers that be who planned the event touted the fair as "The World of Tomorrow, and the Doughnut Corporation of America was on hand to put a sugary perk in people's steps as they wandered in and out of possibilities in the Food Zone.

In the prior World's Fair in 1933, the food and agriculture displays stopped residing in the same building for the first time, representing a shift in the way people thought about food production. Processed foods and drinks, like Coca-Cola, Wonder Bread, and, of course, donuts, made by food processors and scientists, not farmers, were on the '39 fair's menu to save fair-goers from hunger. During that time, an advertisement for Mayflower Donuts and Maxwell House Coffee appeared on the front cover of a menu for the Mayflower Donuts shops. It was the kind of cheery optimism that allowed people to forget that the Great Depression was only just behind them and another world war loomed close on the horizon.

Donuts came to stand for patriotism and progress

In the realms of patriotism and progress, you'd be hard-pressed to find a more hard-working food than the donut. During both World Wars I and II, donuts symbolized comfort for the troops in the trenches and the binding glue that created the bonds between people. Case in point? Irving Berlin's 1942 musical "This is the Army" contains an ode to lost love "I Left My Heart At The Stagedoor Canteen" in which he wrote, "I kept her serving doughnuts till all she had were gone. I sat there dunking doughnuts till she caught on." Following the war years, John F. Kennedy made his famous "Ich bin ein Berliner" speech, in which, instead of implying that he was a spiritual citizen of Berlin, he declared himself a jelly donut. All of this occurred thanks to a misunderstanding of the German language by a media ready to oversimplify the meaning of his words and to overlook the symbolism behind the president's words during a strained moment of the Cold War.

Concurrent with these happenings, societal progress disguised as the O-ring pushed on. The 1939 Expo certainly didn't hurt the donut's chance to become the next "IT" thing, and given that the Expo itself was called "The World of Tomorrow," it's hard not to make the connection between donuts and progress. Aside from this, many of the most beloved donut companies of today were established during those years: Krispy Kreme in '37; Winchell's and Dunkin' Donuts in '48to name but a few.

Flavored donuts evolved in the 1960s

Maple bars. Chocolate donuts. Bavarian creme. That there are so many popular types of donuts is no big deal for the modern donut eater, but when Dunkin' Donuts introduced its 52 flavors as part of its franchising deals, it represented a new day in donut marketing and taste. As if all that sugar and fat weren't an addicting enough reason to entice donut eaters to visit their local Dunkin' Donuts on the regular, the promise of a new flavor of donut every week, 52 weeks a year, certainly was.

This new-donut-flavor-each-week deal came about when DD's first franchise opened in 1955 in Dedham, Massachusetts. All of this arose from an earlier realization on the part of DD's owner, William Rosenberg, who in 1948 noticed that most of the sales coming from his food truck and eventual shop, Open Kettle, were donuts and coffee. Eventually, Open Kettle morphed into Dunkin' Donuts and the introduction of new donut flavors took customers' donut shop expectations to the next level.

Donuts take off in Japan

Donuts are having their day in Japan. A trip to a Japanese donut shop nets the ardent donut lover a plethora of ingredients to try, each of which promises to give the eater a distinctly Japanese taste experience. Or, as the case may be, the opportunity to get a taste of home should homesickness arise during a trip abroad to the Land of the Rising Sun. To understand why, it's best to look at some donut ingredients. The bumpy circular Japanese mochi donut comes from glutinous rice flour and the Pon de Ring donuts care of Mr. Donut are made from tapioca flour. The plethora of ingredients gives each donut a distinct flavor and texture. This isn't to say that Japan only has Mr. Donut to choose from. American imports, Krispy Kreme and Dunkin', and home-grown offerings, like Miel Baked Donut, are just a few of Japan's other donut offerings.

However, for those who love all things Japanese, Mr. Donut, which was founded in 1980, offers some additional enticements. Its collaboration with the Pokémon brand is case in point. This collaboration brought with it Pikachu-shaped donuts and other specialty items, which Mr. Donut rolls out a couple of times a year.

Donut variations around the world

When a recipe crosses international borders, cultural preferences, ingredient availability, and the passage of time change it, and the donut is no exception to this. While Americans may love a good glazed or creme-filled donut, the preferences of the U.S. donut-eating population don't always translate over to other cultures.

In China, for instance, pork and seaweed donuts rule the day. In other parts of Asia, people eat jalebi, which includes ingredients like saffron, ghee, plain yogurt, and rose essence. In Indonesia, donut lovers enjoy donuts with a bit of cheese to liven things up a bit. Spanish and Mexican culture produced churros, and the Bulgarians are known for their kanzanlak donuts. Each of these different donut types offers a flavorful record of how the basic recipe for fried bread has morphed and changed around the world. When looked at through this lens, it's not so difficult to see how the honey cakes of old eventually became the donuts people know and love today.