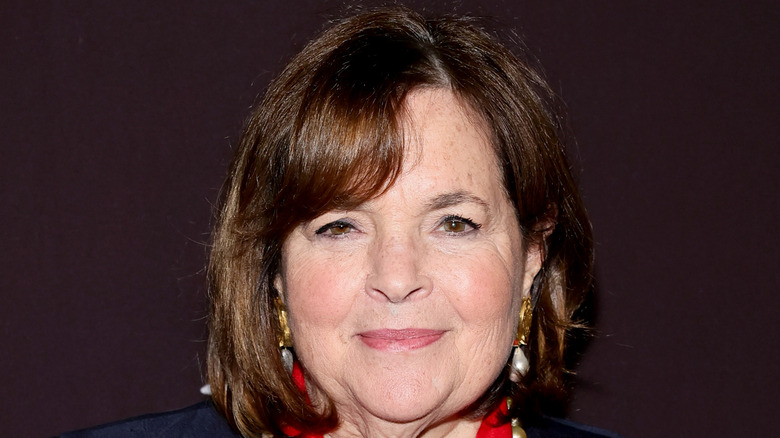

Why Ina Garten Intentionally Undercooks Her Chicken

Chicken is notoriously tricky to cook well. Even if you take it off the heat the moment it hits the USDA-recommended 165 degrees Fahrenheit, it will likely be overcooked by the time it hits the table thanks to a process called carryover cooking (in which food removed from heat continues to cook residually). To combat this, Ina Garten never removes the skin from chicken breasts and deliberately undercooks them to between 155 and 160 degrees Fahrenheit. Let's be clear, though: The Barefoot Contessa isn't serving undercooked poultry (which would be dangerous). There's an important distinction between taking your bird off the heat before it's fully cooked and serving it before it's fully cooked.

In a video posted to Instagram, Garten shared some "tips for flavorful, moist chicken breasts" and explained that she rests them for about 10 minutes under foil so they can come up to temperature as they sit. She shares that, as a result, "all the juices get back into the chicken. You won't believe what a difference it makes."

By removing the chicken from the oven a few minutes early, the residual heat won't overcook it. Instead, it will turn out succulent and flawlessly cooked through. That's why Garten takes hers out early rather than serving it piping hot — to finish it gently. If you harness the power of residual heat and use carryover cooking to your advantage, you'll never serve overcooked chicken again.

Is this safe?

The USDA recommends cooking chicken to 165 degrees Fahrenheit because that's the temperature at which Salmonella bacteria, a dangerous foodborne pathogen, is instantly killed. It reaches what's called a 7.0 log lethality, which means 99.99% of all Salmonella bacteria die. As long as you have a reliable meat thermometer, this method is foolproof; once the meat reaches 165 degrees Fahrenheit, it's safe.

Additionally, research from Michigan State University published in the International Journal of Food Microbiology shows that you can hold chicken at temperatures lower than 165 degrees Fahrenheit for certain lengths of time and still reach a 7.0 log lethality of Salmonella. Holding it at 160 degrees Fahrenheit for 16.9 seconds achieves this. So does holding it at 155 degrees Fahrenheit for 54.4 seconds or 145 degrees Fahrenheit for 13 minutes. The chicken must maintain this temperature throughout for the appropriate amount of time to be safe to eat. That's why Ina Garten rests her chicken under foil; it helps to hold in heat as the carryover cooking reaches the right time/temp split to kill bacteria without drying out the meat.

As a note, the MSU time scale depends on variables like the fat content of your chicken, which increases the time necessary to kill the bacteria. These figures all assume the highest fat content listed in the study, but you should err on the side of caution by going slightly over the listed time just to be safe.

Garten undercooks chicken to keep it moist

The art of cooking is, at least in part, about perfecting doneness. Overcooked eggs become rubbery, overcooked meat becomes dry. With chicken, cooking exactly to 165 degrees Fahrenheit is well above the threshold of when the meat starts drying out.

Like all meat, chicken is made of muscle fibers and tissue. Both hold moisture, which is lost in two rounds. When the internal temperature reaches 104 degrees Fahrenheit, moisture is squeezed out of the muscle fibers and moves into the tissue; at 154 degrees Fahrenheit, it's squeezed out of the tissue, too — and out of the meat entirely. As internal temperatures rise, the moisture loss increases. According to a 2020 study published in Poultry Science, chicken cooked to 175 degrees Fahrenheit loses roughly 15% to 20% more moisture than chicken cooked to 165 degrees Fahrenheit; if you take it off the heat right at 165 degrees Fahrenheit, the temperature will keep rising through carryover cooking and the meat will continue to dry out.

By stopping at 155 degrees Fahrenheit and resting the chicken under foil, Ina Garten's technique minimizes dryness by not rocketing over the range for optimal doneness. By using the timetable from Michigan State University and Ina Garten's residual heat technique, you can optimize for both juicy chicken and food safety — hold it at 153 degrees Fahrenheit for 1.6 minutes, and it won't reach the 154-degree moisture-loss threshold, but it will have reached the 7.0 log lethality of Salmonella threshold.

How carryover cooking works

Carryover cooking is just physics, but gaming carryover cooking like Ina Garten requires you to understand it. The second law of thermodynamics says that heat will always flow to colder areas. During cooking, heat moves through the outer layer of the chicken, spreading to the interior. When taken away from the heat source, the area that had contact is still hotter; some of that heat will dissipate into the cooler air of your kitchen (that's why you can feel it radiating), but some will continue to move inward until it equalizes. (This is why you always take temperature readings from the center.)

According to tests run by Thermoworks, the hotter the cooking temp, the more carryover cooking there is — a piece of chicken cooked at 300 degrees Fahrenheit will rise by 8 degrees Fahrenheit. Cooked in a 425-degree-Fahrenheit oven, though, the internal temperature can rise up to 13 degrees Fahrenheit. But that doesn't mean you can stop cooking once the chicken hits 152 degrees Fahrenheit and trust it.

Although you can count on carryover cooking, you can't always plan for it safely because of how many variables there are. The temperature of your kitchen will affect it. The cut will, too: The denser the meat, the more thermal mass it carries. A whole roasted chicken will endure more carryover cooking than thin cutlets. If you're tempted to cook chicken like Garten, always use a meat thermometer and keep an eye on the time and temperatures.